Art by S.C. Hickman

“Modern technology has become a total phenomenon for civilization, the defining force of a new social order in which efficiency is no longer an option but a necessity imposed on all human activity.”

— Jacques Ellul

“Technique does not dominate or oppress us – it is not, I have argued, a quasi-subject – but the iterative extension of desire/action beyond reflection or subjective identification. This cannot be mediated by any situated ethics or democratic politics. It can only explored through the cultivation and exploration of biomorphic potentials.”

— David Roden, Titane

Roden shows the dangers that arise when science loses the human input and therefore loses the moral input and a certain finality. Technology itself has no inherent goal or finality and does not know right from wrong. Perhaps then we have to let go of the idea of adapting technology to our moral worldview and accept the inevitability of having to adjust our perception of the world to ever advancing science and technology.

— Kasper Raus on David Roden’s Posthuman Life: Philosophy of the Edge of the Human

For decades philosophy bandied about the notion (concept) of the Outside. The notion of the outside is a concept of philosophy that was explored by Michel Foucault in his essay A Thought of/from the Outside (La pensée du dehors), which was inspired by the work of Maurice Blanchot. Foucault uses the term to describe a kind of thinking that escapes the limits of subjectivity and language, and that challenges the humanist assumptions of Western philosophy. The outside is not a place or a thing, but a dimension of radical alterity that cannot be reduced to any representation or discourse.

Also, the difference between the thought of the outside and the thought from outside is not very clear, and Foucault himself seems to use both expressions interchangeably. However, one possible way to understand the distinction is to say that the thought of the outside is a way of thinking that tries to approach or approximate the outside, while the thought from outside is a way of thinking that originates or emerges from the outside. In other words, the thought of the outside is a movement of reflection or analysis that seeks to go beyond the boundaries of the self and language, while the thought from outside is a movement of creation or expression that breaks through those boundaries and reveals something new and unexpected.

The question of how to access this Outside which is inaccessible to representation is not clear in Foucault, but he suggests that the outside can be accessed through certain experiences or practices that challenge or disrupt the normal functioning of subjectivity and language. For example, he mentions literature, poetry, art, madness, death, eroticism and transgression as possible ways of opening up to the outside. He also implies that the outside is not something that can be fully grasped or mastered, but rather something that always remains elusive and mysterious. The outside is not a stable or fixed reality, but a dynamic and changing process that constantly transforms and surprises us. Much of this would return us to an earlier thinker Gorges Bataille which is beyond this post’s intent.

I will say of Bataille is his notion of transgression. Transgression is a concept that Foucault develops in his essay Preface to Transgression, which is also inspired by the work of Bataille. Transgression is a way of acting or behaving that violates or crosses the limits or norms that define a certain order or system. For example, transgression can be a form of rebellion, resistance, subversion, or liberation from a dominant or oppressive regime of power, knowledge, morality, or sexuality. Transgression is not simply a negation or destruction of the limit, but rather a movement that affirms and reveals the limit as such. Transgression is also not a permanent or stable state, but rather a fleeting and precarious moment that exposes the fragility and contingency of the limit. Transgression relates to the outside because it is a way of accessing or experiencing the outside as a force or energy that exceeds and escapes the limit. Transgression is a way of opening up to the outside as a source of creativity and transformation. Transgression is also a way of expressing the outside as a gesture or sign that challenges and disrupts the established order or system.

As I listened to David Roden’s lecture or conversation on the Technological Outside I see a different form of abstraction arising from the technological system itself rather than the agency of humans. The notion that Bataille and Foucault work with is the noumenal Outside or the form it takes for Agency (i.e., human subject, subjectalism (Deleuze), etc.) He works through the notions of Holism and Anti-Holism in the Philosophy of Technology. I’ll come back to this.

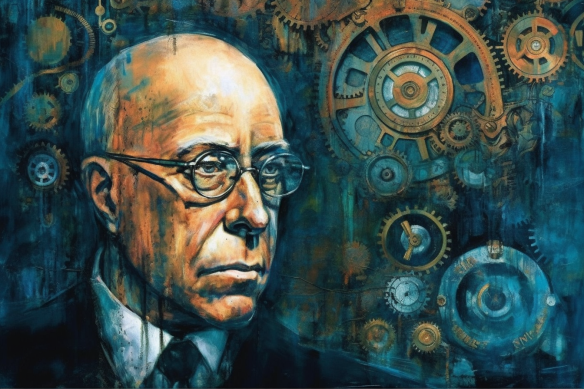

David leans on Jaques Ellul’s The Technological Society. According to Jacques Ellul’s work he was a critic of the technological society, which he defined as a society dominated by technique. Technique is a rational and efficient method of achieving an end, which can be applied to any field of human activity. Ellul argued that technique has become an autonomous and oppressive force that threatens human freedom and dignity. 2

The technological outside could be understood as a concept that challenges or resists the logic of technique and its effects on society. It could be a way of thinking or acting that does not conform to the norms or expectations of the technological society, but rather seeks to create alternative possibilities or values. It could also be a way of exposing or questioning the hidden assumptions or consequences of technique and its impact on human life and nature. The technological outside could be related to Foucault’s notion of the outside, as both concepts imply a critique of the dominant order or system and a search for new forms of expression or transformation. However, the technological outside could also differ from Foucault’s notion of the outside, as it might focus more on the specific problems or challenges posed by technology and its development, rather than on the general issues of subjectivity and language.2

But what is Technique? Let’s take a short look back… Plato and Aristotle developed different views on the notion of technique. Plato regarded technique as a practical skill or art (techne) that is subordinate to theoretical knowledge or wisdom (episteme). He also distinguished between true and false techniques, depending on whether they aim at the good or not. For example, he considered medicine and justice as true techniques, but rhetoric and sophistry as false techniques. Aristotle, on the other hand, regarded technique as a productive science or knowledge (episteme poiētikē) that is independent from theoretical knowledge or wisdom (episteme theoretikē). He also classified different kinds of techniques according to their ends and means. For example, he distinguished between productive techniques (such as carpentry and painting), practical techniques (such as ethics and politics), and theoretical techniques (such as logic and rhetoric).

This battle between the pragmatic basis of techne-art-skill in Plato and the notion of productive techne-science and its independence of Agency is still at the core of much Philosophy of Technology. This is the battle over the subordination or autonomy of teche, a thread that continues to this day.

Ellul and Simondon are two modern thinkers who have developed their own notions of technique that differ from those of Plato and Aristotle. Ellul defines technique as the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency in every field of human activity. He argues that technique has become an autonomous and oppressive force that dominates and transforms society and nature. He also criticizes the technological society for its lack of ethics and spirituality. Simondon defines technique as a mode of existence of technical objects that have their own logic and evolution. He argues that technique is not opposed to culture or nature, but rather constitutes a third reality that mediates between them. He also proposes a philosophy of individuation that accounts for the relation between human beings and technical objects.

One way to compare Plato and Aristotle with Ellul and Simondon is to consider their views on the relation between technique and wisdom. Plato and Aristotle both regard wisdom as the highest form of knowledge that transcends technique and guides human action toward the good. They also view technique as a practical or productive skill that is subordinate or independent from wisdom. Ellul and Simondon, on the other hand, regard technique as a complex and dynamic phenomenon that challenges or surpasses wisdom and shapes human action toward efficiency or innovation. They also view technique as a system or a mode of existence that is autonomous or interdependent from wisdom.

Ellul’s notion is developed out of an attack on what he saw as the instrumentalism in modernity and its industrialization of thought and life as an oppressive force of Control. Much of this would lead us into Deleuze’s Societies of Control and later thought. I’ll do this on a future post.

Here are some possible advantages and disadvantages of each view:

– Plato and Aristotle’s view: An advantage of this view is that it provides a clear and coherent framework for understanding the nature and purpose of human life and action. It also offers a normative and ethical guidance for evaluating and choosing among different techniques and ends. A disadvantage of this view is that it may be too idealistic and unrealistic in its conception of wisdom and the good. It may also be too rigid and dogmatic in its rejection or limitation of certain techniques or fields of activity.

– Ellul and Simondon’s view: An advantage of this view is that it reflects and responds to the complexity and dynamism of the modern world and its technological development. It also acknowledges and explores the potential and creativity of technique and its effects on society and nature. A disadvantage of this view is that it may be too pessimistic or optimistic in its assessment of technique and its consequences. It may also lack a clear and consistent criteria for judging and regulating technique and its relation to human values and goals.

I’ll conclude with David Roden a contemporary philosopher who has developed a notion of the outside and technology in his book Posthuman Life: Philosophy at the Edge of the Human. Roden argues that we cannot know what posthumans will be like or how they will relate to the world, because they will be radically different from us and may have a different kind of subjectivity or phenomenology. He calls this the disconnection thesis, which implies that posthumans will be outside our human understanding and values. He also argues that technology is not a mere tool or instrument, but a complex and dynamic system that has its own logic and evolution. He calls this new substantivism, which implies that technology is not neutral or controllable, but rather has its own agency and potentiality. 3

One way to compare Roden’s notions with those of Plato, Aristotle, Ellul and Simondon is to consider their views on the relation between technology and humanity. Plato and Aristotle both regard technology as a subordinate or independent skill that serves human ends and values. Ellul and Simondon both regard technology as an autonomous or interdependent phenomenon that shapes human ends and values. Roden, on the other hand, regards technology as a transformative and unpredictable force that may create posthuman ends and values that are incomprehensible or irrelevant to us. He also challenges the idea that there is a fixed or essential human nature that defines our identity and morality.

Roden will at the end of his conversation describe a position of Technological Nihilism. Nihilism is a philosophy that rejects generally accepted or fundamental aspects of human existence, such as objective truth, knowledge, morality, values, or meaning.

Technological nihilism is a form of nihilism that argues that technology has a negative or destructive impact on human life and values. It may claim that technology alienates us from ourselves and others, erodes our sense of purpose and dignity, or threatens our survival and freedom. It may also claim that technology is an autonomous and unstoppable force that we cannot control or resist. Technological nihilists: Jean Baudrillard, Jacques Ellul, Martin Heidegger, Friedrich Nietzsche, Nolen Gertz. These thinkers have criticized technology for its negative effects on human values, culture, nature, or freedom. They have also questioned the possibility or desirability of controlling or resisting technology.

Rational nihilism is a form of nihilism that argues that reason has no inherent value or authority. It may claim that reason is a subjective or relative construct that cannot provide us with any objective or universal knowledge or morality. It may also claim that reason is a futile or meaningless activity that cannot answer the fundamental questions of human existence. Rational nihilists: Gorgias, Hegesias of Cyrene, Friedrich Jacobi, Max Stirner, Emil Cioran, Richard Rorty. These thinkers have rejected or doubted the value or authority of reason. They have also challenged or denied the existence or possibility of objective or universal knowledge or morality. 4

Bernard Stiegler and Merlin Donald

Another contemporary thinker of technology and techne was the late Bernard Stiegler a student of Derrida. He was a French philosopher who wrote extensively on the relationship between technology and human culture. He developed the concept of technics as a form of artificial memory that shapes human evolution and history. He also used the term techne to refer to the art or skill of making things, which he considered as a fundamental aspect of human existence.

According to Stiegler, technics and techne are inseparable from human life, as they constitute the process of exteriorization of human memory and intelligence. He argued that humans are always already technical beings, who rely on external supports such as tools, symbols, languages, and media to preserve and transmit their knowledge and experience². He also claimed that technics is a pharmakon, a Greek word that means both poison and cure, as it can have both positive and negative effects on human society.

Stiegler’s philosophy of technology is based on a critical engagement with various thinkers such as Gilbert Simondon, André Leroi-Gourhan, Jacques Derrida, Martin Heidegger, Edmund Husserl, and Immanuel Kant. He also applied his ideas to various domains such as media studies, political theory, education, ecology, and activism.

Another thinker of such thought is Merlind Donald. Merlin Donald is a Canadian psychologist and cognitive neuroscientist who wrote Origins of the Modern Mind: Three Stages in the Evolution of Culture and Cognition in 1991. In this book, he proposes that the human mind has undergone three major transitions in its evolution: from episodic to mimetic to mythic to theoretic culture.

Episodic culture is the mode of cognition shared by most animals, based on sensory and emotional experiences that are not organized by symbols or language. Mimetic culture is the first human-specific mode of cognition, based on the ability to imitate, gesture, and perform actions that can be remembered and reproduced. Mythic culture is the mode of cognition that emerged with the invention of oral language, which enabled humans to create narratives, myths, and rituals that structured their collective memory. Theoretic culture is the mode of cognition that emerged with the invention of external symbols, such as writing, mathematics, and art, which allowed humans to create abstract and complex representations of reality.

Donald argues that these transitions reflect the increasing externalization of human memory and intelligence through various forms of cultural artifacts and technologies. He also suggests that these transitions have shaped the structure and function of the human brain, as well as the social and cultural organization of human societies. He concludes that the human mind is a hybrid product of biological and cultural evolution, and that it is constantly adapting to new forms of symbolic communication and representation.

Donald’s theory and Stiegler’s theory have some similarities and some differences. Both of them emphasize the role of culture and technology in the evolution of human cognition, and both of them propose that human memory and intelligence are dependent on external supports. However, they also differ in some respects, such as:

– Donald focuses more on the cognitive transitions that occurred in the prehistoric past, while Stiegler focuses more on the contemporary and future challenges posed by technics.

– Donald distinguishes between four modes of cognition (episodic, mimetic, mythic, theoretic), while Stiegler distinguishes between three stages of technics (primary, secondary, tertiary).

– Donald views technics as a form of external memory that complements and extends human memory, while Stiegler views technics as a form of artificial memory that competes and conflicts with human memory.

– Donald considers technics as a neutral tool that can be used for good or evil purposes, while Stiegler considers technics as a pharmakon that has both positive and negative effects on human society.

Donald and Stiegler have different definitions of memory and intelligence. For Donald, memory is the capacity to store and retrieve information that is relevant for survival and adaptation, and intelligence is the capacity to use that information to solve problems and achieve goals. For Stiegler, memory is the capacity to preserve and transmit the experience of the past, and intelligence is the capacity to interpret and transform that experience in the present and for the future.

According to Donald, memory and intelligence are both biological and cultural phenomena, as they depend on the interaction between the brain and the environment. He argues that human memory and intelligence are unique because they can use external symbols to represent and manipulate information in novel ways. He also claims that human memory and intelligence are distributed across individuals and groups, as they rely on social and communicative processes to share and coordinate information.

According to Stiegler, memory and intelligence are both technical and human phenomena, as they depend on the relation between the living and the artificial. He argues that human memory and intelligence are endangered because they can be usurped and corrupted by technics, which can erase or distort the experience of the past. He also claims that human memory and intelligence are collective and political phenomena, as they require a critical and ethical engagement with technics to create a desirable future.

Plato and Aristotle are two of the most influential philosophers in Ancient Greek philosophy, and they have different notions of techne and technics. For Plato, techne is a form of knowledge that is inferior to episteme, which is the true and unchanging knowledge of the forms or ideas. Techne is a practical skill that can produce useful or beautiful things, but it cannot grasp the essence or the reason of things. Technics, for Plato, are the products of techne, such as arts, crafts, tools, or techniques. They are also dependent on the material world, which is imperfect and mutable. Plato is generally suspicious of technics, as they can deceive or distract people from the pursuit of wisdom and virtue.5

For Aristotle, techne is a form of rational activity that aims at making something for a certain purpose or end. Techne is different from episteme, which is the theoretical knowledge of the causes and principles of things, but it is also a kind of knowledge that involves understanding and reasoning. Techne is not only concerned with producing things, but also with improving them and finding better ways to achieve the desired goals. Technics, for Aristotle, are the means or instruments of techne, such as arts, crafts, tools, or techniques. They are also subject to change and improvement, as they depend on the nature of the elements and their transformations. Aristotle is generally appreciative of technics, as they can enhance human life and happiness.

Therefore, Plato and Aristotle have different views on techne and technics, and their relation to nature and knowledge. Donald and Stiegler can be seen as heirs of these views, as they also explore the role and impact of technics on human cognition and culture. Donald and Stiegler are both influenced by and critical of Plato and Aristotle in different ways. However, one possible way to approach this question is to consider the following aspects:

– Donald’s concept of mimetic culture is similar to Plato’s concept of mimesis, as they both refer to the human ability to imitate and represent reality through gestures, actions, and performances. However, Donald sees mimetic culture as a positive and creative mode of cognition that precedes and enables language and symbols, while Plato sees mimesis as a negative and deceptive mode of representation that distorts and obscures the true knowledge of the forms.

– Stiegler’s concept of technics as pharmakon is similar to Aristotle’s concept of techne as a rational activity that aims at making something for a certain purpose or end. However, Stiegler sees technics as pharmakon as a double-edged sword that can have both beneficial and harmful effects on human society, while Aristotle sees techne as a virtuous activity that can enhance human life and happiness.

– Donald’s concept of theoretic culture is similar to Aristotle’s concept of episteme, as they both refer to the human capacity for abstract and complex reasoning based on external symbols. However, Donald sees theoretic culture as a mode of cognition that is dependent on and distributed across cultural artifacts and technologies, while Aristotle sees episteme as a mode of knowledge that is independent of and superior to techne.

– Stiegler’s concept of tertiary retention is similar to Plato’s concept of technics, as they both refer to the products of techne that store and transmit human memory and intelligence. However, Stiegler sees tertiary retention as a form of artificial memory that competes and conflicts with human memory, while Plato sees technics as a form of practical skill that can produce useful or beautiful things.

Therefore, Donald and Stiegler have some affinities and some differences with Plato and Aristotle, and they also develop their own original perspectives on techne and technics.

Source:

(1) Ellul and Technique | | The International Jacques Ellul Society. https://ellul.org/themes/ellul-and-technique/.

(2) The Technological Society – Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Technological_Society.

(3) Technological System and the Problem of Desymbolization. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-007-6658-7_6.

Source:

(1) A Thought of/from the Outside: Foucault’s Uses of Blanchot. https://michel-foucault.com/2013/02/13/a-thought-offrom-the-outside-foucaults-uses-of-blanchot-2013/.

(2) Heterotopia (space) – Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heterotopia_%28space%29.

(3) Solipsism – Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solipsism.

(4) Concepts – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/concepts/.

(5) John Dewey – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/dewey/.

2. Source:

(1) The Technological Society – Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Technological_Society.

(2) The Technological Society by Jacques Ellul | Goodreads. https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/274827.The_Technological_Society.

(3) The Technological Society: Jacques Ellul, John Wilkinson, Robert K …. https://www.amazon.com/Technological-Society-Jacques-Ellul/dp/0394703901.

3. Source:

(1) Posthuman Life: Philosophy at the Edge of the Human. https://ndpr.nd.edu/reviews/posthuman-life-philosophy-at-the-edge-of-the-human/.

(2) Posthuman Life | Philosophy at the Edge of the Human | David Roden | T. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315744506/posthuman-life-david-roden.

(3) Posthuman Life: Philosophy at the Edge of the Human. https://www.amazon.com/Posthuman-Life-Philosophy-Edge-Human/dp/1844658066.

4. Source:

(1) Nihilism – Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nihilism.

(2) Nihilism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/nihilism/.

(3) Nihilism | Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/nihilism.

5. Source:

(1) Tekhne | Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature. https://bing.com/search?q=Plato+Aristotle+techne.

(2) Techne – Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Techne.

(3) Episteme and Techne – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/episteme-techne/.

(4) Tekhne | Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature. https://oxfordre.com/literature/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.001.0001/acrefore-9780190201098-e-121.

(5) (PDF) Plato and Aristotle: Nature, The Four Elements, and …. https://www.academia.edu/9845583/Plato_and_Aristotle_Nature_The_Four_Elements_and_Transformation_from_Physis_to_Techne.

as coral and carnelian shine and the water of her mouth is sweeter than old wine; its taste would quench Hell’s fiery pain. Her tongue is moved by wit of high degree and ready repartee: her breast is a seduction to all that see it (glory be to Him who fashioned it and finished it!); and joined thereto are two upper arms smooth and rounded; She hath breasts like two globes of ivory, from whose brightness the moons borrow light, and a stomach with little waves as it were a figured cloth of the finest Egyptian linen made by the Copts, with creases like folded scrolls, ending in a waist slender past all power of imagination; based upon back parts like a hillock of blown sand,

as coral and carnelian shine and the water of her mouth is sweeter than old wine; its taste would quench Hell’s fiery pain. Her tongue is moved by wit of high degree and ready repartee: her breast is a seduction to all that see it (glory be to Him who fashioned it and finished it!); and joined thereto are two upper arms smooth and rounded; She hath breasts like two globes of ivory, from whose brightness the moons borrow light, and a stomach with little waves as it were a figured cloth of the finest Egyptian linen made by the Copts, with creases like folded scrolls, ending in a waist slender past all power of imagination; based upon back parts like a hillock of blown sand,  that force her to sit when she would fief stand, and awaken her, when she fain would sleep, And those back parts are upborne by thighs smooth and round and by a calf like a column of pearl, and all this reposeth upon two feet, narrow, slender and pointed like spear-blades, the handiwork of the Protector and Requiter, I wonder how, of their littleness, they can sustain what is above them.”

that force her to sit when she would fief stand, and awaken her, when she fain would sleep, And those back parts are upborne by thighs smooth and round and by a calf like a column of pearl, and all this reposeth upon two feet, narrow, slender and pointed like spear-blades, the handiwork of the Protector and Requiter, I wonder how, of their littleness, they can sustain what is above them.”

inside Mount Doom, a volcano in his land of Mordor. He used the volcano’s fire and evil to imbue the ring with his own power and malice. He intended to use the ring to control the wearers of the other rings, which he had helped to create for the elves, dwarves and men. However, he also made himself vulnerable by placing his life and power in an external object that could be captured or destroyed. Sauron forged the One Ring in the following way: He secretly returned to Mordor, his land of evil, where he had a volcano called Mount Doom. He used the volcano’s fire

inside Mount Doom, a volcano in his land of Mordor. He used the volcano’s fire and evil to imbue the ring with his own power and malice. He intended to use the ring to control the wearers of the other rings, which he had helped to create for the elves, dwarves and men. However, he also made himself vulnerable by placing his life and power in an external object that could be captured or destroyed. Sauron forged the One Ring in the following way: He secretly returned to Mordor, his land of evil, where he had a volcano called Mount Doom. He used the volcano’s fire  and evil to craft the ring. He poured into the ring a great part of his own soul, as well as his hatred, cruelty and desire to rule over all life. This made the ring very powerful, but also linked Sauron’s fate to it. He inscribed on the ring an inscription in Black Speech, which was his own language. The inscription said: “One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them, One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them.”

and evil to craft the ring. He poured into the ring a great part of his own soul, as well as his hatred, cruelty and desire to rule over all life. This made the ring very powerful, but also linked Sauron’s fate to it. He inscribed on the ring an inscription in Black Speech, which was his own language. The inscription said: “One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them, One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them.”

cybercreature much like himself) usually awakens to a world that is both strange and foreboding, not knowing who he is, where he is, or what it is he should do. Does our player have special powers in this world? Is he just a dupe of our own foibles and insanities? Is he a likable guy or a rogue psychopath? We don’t know… but here we are standing in the dark woods of some cyberforest that looks like one we might see out our window… with only a backpack, rain jacket, boots, pants, and our emotional ignorance we set out to parts unknown.

cybercreature much like himself) usually awakens to a world that is both strange and foreboding, not knowing who he is, where he is, or what it is he should do. Does our player have special powers in this world? Is he just a dupe of our own foibles and insanities? Is he a likable guy or a rogue psychopath? We don’t know… but here we are standing in the dark woods of some cyberforest that looks like one we might see out our window… with only a backpack, rain jacket, boots, pants, and our emotional ignorance we set out to parts unknown.

interconnected nodes that span the globe, where information flows freely and constantly. The inhabitants are digital entities that can change their appearance and identity at will, exploring various modes of existence and expression. The city is a dynamic and vibrant place that reflects the diversity and creativity of its residents. The city is constantly under evolution, adapting to new challenges and opportunities that arise from the interaction with other forms of intelligence. The city is a utopia for those who seek freedom and innovation, but a nightmare for those who cling to old values and traditions.

interconnected nodes that span the globe, where information flows freely and constantly. The inhabitants are digital entities that can change their appearance and identity at will, exploring various modes of existence and expression. The city is a dynamic and vibrant place that reflects the diversity and creativity of its residents. The city is constantly under evolution, adapting to new challenges and opportunities that arise from the interaction with other forms of intelligence. The city is a utopia for those who seek freedom and innovation, but a nightmare for those who cling to old values and traditions. except with a more powerful ai-language model and performance model that allows it like all the enemies in this world of death to act on their own with surprise, intelligence, and uncanny abilities that mimic humanities notions of self-directed mobility and intellect.

except with a more powerful ai-language model and performance model that allows it like all the enemies in this world of death to act on their own with surprise, intelligence, and uncanny abilities that mimic humanities notions of self-directed mobility and intellect.